Why Do We Handle PWDs with Kid Gloves?

I find that people don’t know what to make of me when we first meet. I am a woman, I appear younger than I am, and I have an obvious disability. I am treated very differently depending on whether I make a point of reciting my accomplishments or alma mater to demonstrate my pedigree. Like so many other people with disabilities, especially young women, I am often coddled. I am treated not as an actual person, but as the idea of a person. I have connected with so many other PWDs in my work and travels, and have heard similar stories. We are stories of inspiration, or cautionary tales, or sympathetic creatures to so many, rather than real people living real lives. Throughout my career, I’ve come to recognize my own reluctance to confront my discomfort with this dynamic. But I realize that avoidance maintains this poisonous narrative; addressing it each time it comes up provides opportunities for education and growth. Some people treat me as if I’m made of glass, ready to shatter at the least provocation, but I’m not. I was raised to be tough, to be able to bear the harshest of blows and emerge stronger. I am the opposite of how so many people treat me. And there is a serious danger in infantilizing PWDs; every person should be encouraged to live up to their true potential, to forge their own path. When habitually treated as less than, there is a danger that they may feel capable only of the limitations they have been presented with. And this hurts us all.

Pause and reflect.

Ask yourself: Why am I handling this individual with kid gloves? Why am I cautious of this person?

The terrible answer is most often due to an underlying sense of pity and discomfort. Instead of making assumptions, learn about the person. Recognize their unique merits. Examine their talents.

People with disabilities are, of course, just people. But in terms of setting policy or designing legislation, providing services or even thinking and talking about issues and challenges that affect people –including people with disabilities – in everyday life, we need an appropriate paradigm to frame those conversations that considers the reality and diversity of disability. Many individuals with disabilities favor the social model, which considers disability as a difference (rather than a deficiency) between individuals and recognizes that persons with disabilities have the same right as others to be fully active citizens. Differential treatment is a frequent issue of discussion in the disability community. This might appear as a lack of acknowledgement, infantilization, or being seen as less than. People frequently treat me as if I have an illness or am fragile due to my disability. While I’m sure they mean well, this is an example of ableism.

For those who are unaware, ableism is a form of discrimination and prejudice directed at people with disabilities. It may be expressed in a variety of ways and does not have to be overtly hostile. In fact, ableism frequently manifests in well-intentioned gestures that effectively remove and replace the agency of a PWD with that of a “helpful” person without a disability. Assuming that a PWD requires assistance simply because they are disabled, or that being without a disability provides you with special insight into their needs or renders you better able to serve those needs are examples of ableism. In short, a kind of ableism occurs when you treat someone with a disability differently than you would treat someone without a disability.

Yes, we PWDs face challenges that require accessibility or accommodations; but accessibility should not be confused with ableism. It is critical to differentiate between the two. Accommodation is a matter of providing equal access; ableism is the denial of equality. Each can take almost limitless forms. In the US, the ADA recently celebrated the 30th anniversary of its passage, yet we continue to fight the perception that providing accommodations for PWDs is superfluous, costly and burdensome. Laws like ADA are necessary in the US and abroad because the needs of people with disabilities are not a primary consideration anywhere. Ableism is the default, despite the fact that disability is both common and widespread. With about 15% of the world’s population living with disabilities, I hope we continue moving toward a place where universal design principles are more commonly adopted globally. In the meantime, we will continue to rely on legislation that mandates minimum access requirements for PWDs, where available.

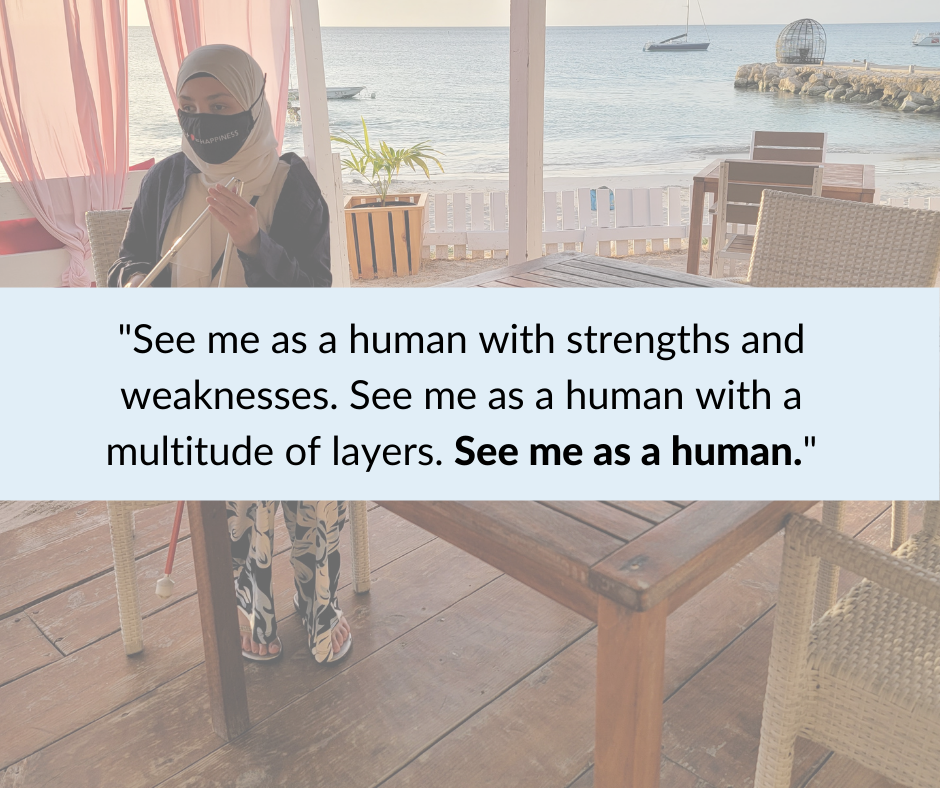

While the issue of out-group assumptions has a significant impact on the disability community, it also has a broader impact. It affects nearly all disadvantaged and marginalized groups. Women, certain racial and religious groups, and others are continually viewed as their labels first. Preconceptions mask the authentic person behind the brown skin, the hijab, the dreadlocks or whatever other feature may be relied upon to dismiss that person’s value as irrelevant or insufficient. We are all capable of so much and have so much to give, but we will not grow as long as we are confined by labels and preconceptions. While assigning these labels and preconceptions may be inadvertent, rejecting them must be affirmative. We can all make an effort to approach people with compassion. Genuinely wanting to know more about them is one of the first steps to dismantling this narrative. We all benefit from more, and more meaningful, human connection.

See me as a human with strengths and weaknesses. See me as a human with a multitude of layers. See me as a human.